Une vision du livre d'artiste à New York dans les années 70

« Looks Matter » est une exposition construite à partir d’un point de vue personnel, localisé et daté. Tim Maul est un artiste photographe et un critique d’art qui vit et travaille à New York. Dans un texte, qui constitue le point de départ de cette exposition, il nous livre son appréciation personnelle du livre d’artiste dans l’atmosphère New Yorkaise des années 70, au fil des rues, des galeries, des librairies et des expositions. S’y côtoient les ouvrages théoriques (Six Years : The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 de Lucy Lippard), les magazines (Avalanche, Aspen...), les publications collectives (Art & Language) et les livres d’artistes du moment : John Baldessari, Richard Hamilton, Les Levine, Ed Ruscha, William Wegman, Lawrence Weiner, entre autres. L’exposition propose une dilatation du focus et étend sa portée tant géographiquement, en présentant les expériences simultanées d’artistes outre - atlantique, que chronologiquement, en développant les continuités du propos liminaire : de Richard Long à Sophie Calle en passant par Jean Le Gac, Annette Messager, Christian Boltanski ou Richard Prince. En parallèle de ce corpus, est présenté le travail de Tim Maul en tant qu’artiste, utilisant la photographie comme medium privilégié pour mettre en scène un récit. Gus V.S./Kodak Paper/81' donne à voir une narration vaguement romantique, questionnant la production d’images, à travers la déambulation d’un individu, « joué » par son ami Gus Van Sant, portant une boîte de papier Kodak. « Rétrospectivement, je vois ces images comme un « au revoir » à la jeunesse, à la banlieue et à l’art des années 70. J’y vois aussi l’influence des Brueghel, jeune et vieux, dont les peintures m’ont toujours intrigué ». Tim Maul est également l’auteur d’un portfolio The cultured tourist. (Curtains) (1996) et d’un livre Traces & Presence (1999), publiés aux éditions Florence Loewy.

|

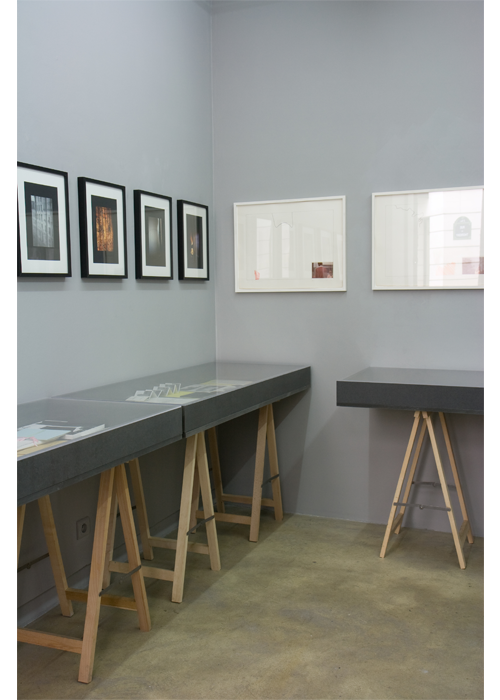

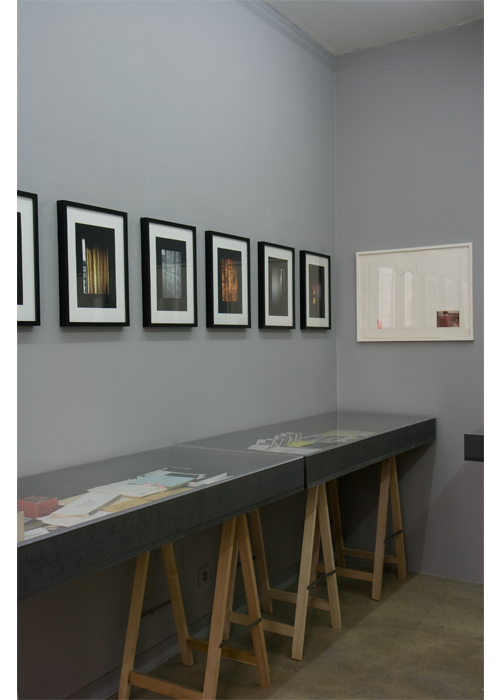

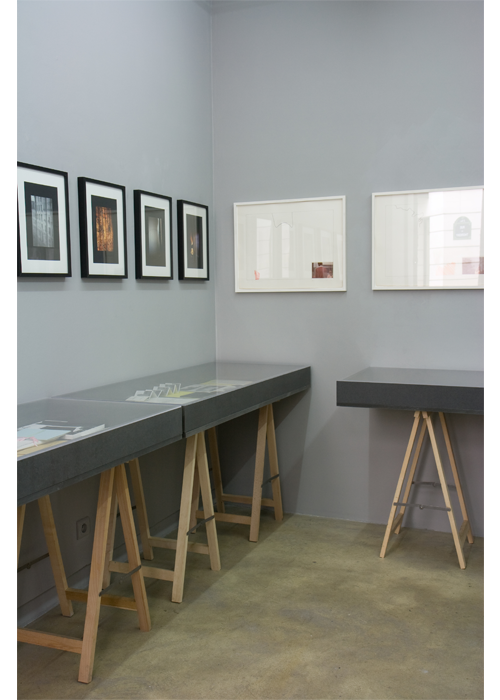

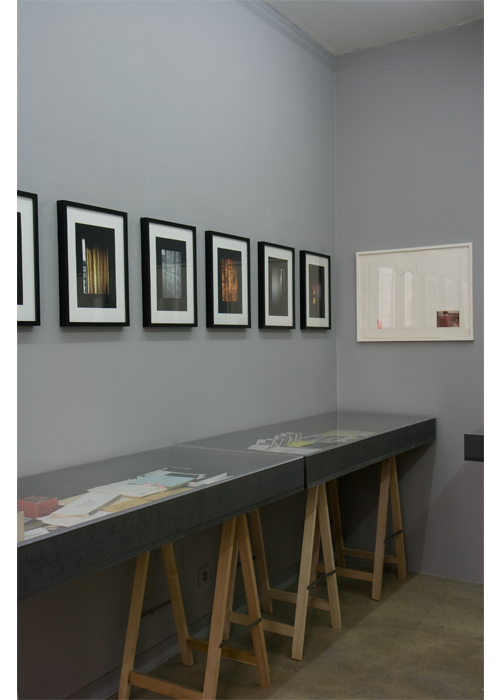

Tim MAUL. The cultured tourist. (Curtains). Paris, 1996, 39 x 30 cm, boîte à archives avec étiquette pour le titre.

Sept tirages cibachromes accompagnés d'un texte de l'artiste, numérotés et signés.

Edition de 10 exemplaires + 2 E.A.

|

|

|

|

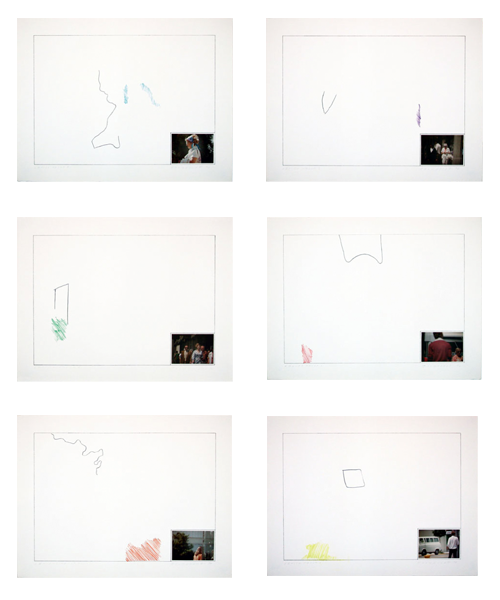

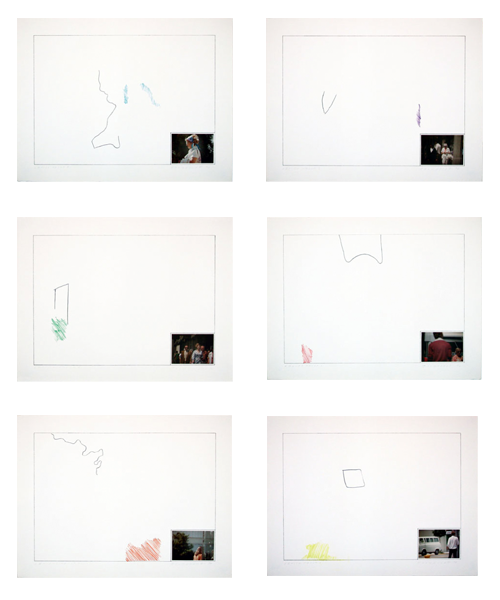

John BALDESSARI. Raw Prints, 1976 John BALDESSARI. Raw Prints, 1976

Lithographie et tirage photographique

46,9 x 62,2 cm

Edition de 50 exemplaires + 12 E.A.

|

Avec les livres d'artistes de /

Vito ACCONCI, John BALDESSARI, Christian BOLTANSKI, Barbara BLOOM, Marcel BROODTHAERS, Sophie CALLE, Jan DIBBETS, Jochen GERZ, Richard HAMILTON, Nancy HOLT, Douglas HUEBLER, Peter HUTCHINSON, Les LEVINE, Jean LE GAC, Sol LEWITT, Richard LONG, Gordon MATTA-CLARK, Annette MESSAGER, Dennis OPPENHEIM, Richard PRINCE, Allen RUPPERSBERG, Edward RUSCHA, Gerry SCHUM, Andy WARHOL, William WEGMAN.

|

|

The following is a personal appreciation and should not be regarded as scholarship. Upon leaving the School of Visual Arts in New York in spring ’73 I wanted to assert myself in the local art world not as a painter or sculptor but as an artist that worked in the nascent category of media. As pop LP’s once had functioned for me, I regarded independent artist publications as viable hand held art experiences communicating significant ‘ideas’. I do not remember where I first encountered Ed Ruscha’s books but their intentions were equal to anything I had experienced hung on a wall or occupying an area of floor. In them I believed that the space of the page and the gallery could change places. I value my own small collection of artist books and ephemera from that socially accessible but highly competitive era. With few exceptions all of my books were purchased below 14th St. in Manhattan at Jaap Rietman’s bookstore on the corner of Spring St. and West Broadway in Soho, or at MOMA’s small bookstore off its 53rd St. lobby entrance. The stack of ‘white cube’ galleries that had opened at 420 West Broadway (Castelli, John Weber, and Sonnabend) made gallery publications and posters available near the front desks, but I would have been too intimidated to make any enquiry toward the purchase of anything at these mysterious gateways to culture. Rietman offered literature, catalogues, magazines and ‘artist books’ which were segregated from the shelved main stock on separate tables. These stacks of slim tomes were not novelty ‘impulse’ purchases positioned by the cash register or promotional giveaways like Warhol’s charming hand colored ‘books’ of the 50’s. Multi-leveled and neatly arranged on a table they recalled the towers in a Lewitt open cube sculpture. Consistent among them was their simplicity and clean production.

Graduating high school in 1969 I absorbed the visual style of the psychedelic ‘counter-culture’ which interfaced art noveau design and cluttered Victoriana with eyeball burning color. The ‘hot’ 60’s cooled off rapidly- “The 70’s are very empty” announced Warhol himself. Album cover art anticipated this; compare Peter Blake’s famed ‘Sgt. Pepper’ cover for The Beatles (’67) to Richard Hamilton’s ‘White Album’ design from 1968, a single year later. Hamilton’s (who awaits serious re-evaluation) blank, shiny white cover with the bands name in raised lettering referenced the ‘bootleg’ album’s appearance along with the artists own ‘finish-fetish’. It also predates the austere if not chilly, ‘golden age’ of artist publications. Hamilton certainly knew of Ruscha’s book published by the artist since the mid-1960’s and his own intimate and amusing ‘Polaroid Portraits’ (’72) is a classic of this era.

I found official conceptual art’s visual reserve and pompous language thrilling in the aftermath of the mellow 60’s. The delay of any discernable movement following minimalism combined with the absence of cash permitted low-cost mercantile experiments both in and out of what was then quaintly referred to as the gallery ‘system’. The few books I owned shared a glacially impersonal visual style that the artist Bill Beckley might label ‘puritanical’. My roommate (1972-3) owned a copy of Sol Lewitt’s ‘Arcs, from Corners & Sides, Circles & Grids and All Their Combinations’ (’72), a symphonic execution of its title that was a stoned favorite in our Fort Greene apartment. Lewitt’s ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’ had been published in the first issue of ‘Art & Language’ (May 1969) and their resemblance to biblical law suggested relief from the

Zen-like critical language doled out in art school studios of the time.

Here was someone telling you what and what not to do through a set of actual rules. As a publication ‘Art & Language’ looked threatening, simultaneously suggesting the ecclesiastic, political, and the un-illustrated textbook. What other factors informed this style ‘drained of entertainment’?

The announcement/invitation cards to the initial Arte Povera manifestations? Aspen Magazine? Marvin Israel’s layout for Diane Arbus’s MOMA catalogue?-(a ubiquitous ‘coffee table’ presence of the period signifying hipness; reductive ‘artist books’ would disappear on a coffee table). Or was it simply the economics of the print shop; the more limited the author’s needs the cheaper the production costs. For artists who had purged all but language from their art, the publication in miniaturized form was relatively affordable allowing for ‘cottage industry’ distribution. Other publishing ‘miniatures’ include Edward Gorey’s compact Gothic tales and Mao’s ‘Little Red Book’ treasured by that commune of attractive young people in ‘La Chinoise’. The Christian prayer book or missal must be also considered along with things from “the Fluxus bureau”. In the 1970’s artist books shrank in size while ‘downtown’ galleries took advantage of the slumping real estate market and expanded in square feet. Art that did not require the production of a physical object was forced into a ‘shotgun marriage’ with print media of some kind. Beginning in the 60’s to the present a utopian optimism that all tech is good tech prevails. Instructional art could be transmitted by telephone. The Xerox or copy machine became the new printing press or lithographer’s stone. Published collections of this art like Ursula Meyer’s ‘Conceptual Art’ (’72) and Kynaston McShine’s ‘Information’ show catalogue (MOMA 1970) functioned the same way group shows would for objects. Magazines like Avalanche, Flash Art, and Interfunktionen offered artist’s projects for the page and inclusion in these publications was equal to participating in an international exhibition seen if only by a knowledgeable elite. The galleries advertising in these periodicals featured artists who appeared ‘on tour’ like rock bands and a ‘short list’ of conceptualists quickly emerged. Lucy Lippard’s invaluable ‘Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object’ (’73) tells a nearly complete story and is invaluable in its tracking of the varied networks of international shows, publications, and other manifestations. I went to bed hungry so I could buy Avalanche. Avalanche’s design was innovative and illustrated purely by photographic documentation of the ‘body’, ‘earth’, ‘idea’, ‘conceptual’ and genuinely oddball artists in Willoughby Sharp’s and Liza Bear’s circle here and abroad. In the early 80’s Thomas Lawson would publish ‘Real Life’, a ‘Pictures Gen.’ project whose bland layout, in comparison to Avalanche, puzzled me; I respect the law of the jungle where one kind of art displaces another but shouldn’t the house organ pitching regime change at least look good? Perhaps it all comes down to style. Why does some art categorized as ‘conceptual’ resonate with us today while other art remains neglected despite any ‘position’ it once may of held? Did a typography decision guarantee the longevity of some language based art? Why a Lawrence Weiner over a Les Levine? Looks matter, along with a few other things.

MOMA’s 2009 ‘‘Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object’ (’73)exemplified the nomadic lives and the everyday subjectivity operating around the ‘Art & Project’ universe. I visited the show several times and ascertained through its materials (maps, postcards, data, photos, booklets, text, and films) an engagement with a lived in world that would later in that decade be ‘shown the door’ in preparation for the revival of painting.

Art & Project bulletins occupied a messy corner on Jaap Rietman’s table and I regret not buying every single one of them. ‘Narrative’ or ‘Story’ art would emerge from conceptual tendencies dispensing with the photograph as truthful illustration. The work of Beckley, Mac Adams, Laurie Anderson, John Baldesarri, Alexis Smith, Jean Le Gac, Peter Hutchinson, Al Ruppersberg and William Wegman would appear in small catalogues but few books (in the next decade Wegman would create a publishing empire upon his beloved dogs). Their text was meant for the wall. The much revered ‘Pictures’ generation which emerged out of academic pockets of conceptual art and film theory sought the scale, perceived budgetary freedom and audience of cinema. In the early 80’s I conveyed my enthusiasm for print media with a member of this group only to be cautioned that books ‘were 70’s art’. Barbara Bloom is my favored exception with a body of work including films and publication that reflected her exposure to art living in 70’s Amsterdam and as one of the ambitious artists who studied under Baldesarri at Cal Arts in the earlier part of that decade. In the 80’s boom market hefty catalogues became standard freebies handed out to collectors and curators. The laborious ‘handmade’ made a return in Anselm Kiefer’s gargantuan book/objects that weighed as much as an early Richard Serra. ‘Narrative’ art , scorned in the 80’s would re-emerge profitably in the 90’s through the work of Sophie Calle, Lorna Simpson, Felix Gonzalez-Torres and others not unfamiliar with the text and image presentations of a Beckley or Victor Burgin.

Today’s bibliophile stands in resistance to Digital’s eventual destruction of the page. Richard Prince’s vast collection of multi-genre hard copy secures his role as both connoisseur and kindred spirit. Prince’s impressive archive ‘floats all boats’ because an artist of Prince’s stature and shrewdly developed persona (Pervy American Loner) has ‘chosen’ each inclusion as Duchamp did his ‘readymades’. Last summer I read ‘Leave Any Information At The Signal’ (2002 October Books) a collection of interviews with Ruscha that were equally witty and fiercely no-nonsense. The artist fixates on his early books as his most misunderstood and most radical art. Their time-consuming production is explained as purely instinctive operating on ‘blind faith’ with no preconceived expectations of an audience or of their reception; now a major factor in signaling to the artist/provocateur his or her next move. Authentic artist books may come back the way vinyl is. Pulling Ruscha’s ‘Swimming Pools’ (mine in copyrighted 1968) from the shelf I recall its moment of purchase in the last century. My drift was halted. My scrutiny narrowed. My arm extended. My wallet was located. What art is doing those things to me today?

Tim Maul, NY, 2/12

|

|

| |

|

|

Photographies : ©Siobhan Wall |

John BALDESSARI. Raw Prints, 1976

John BALDESSARI. Raw Prints, 1976